NOISE, SIGNAL, SILENCE:

THE UNSPOKEN LANGUAGE OF SEOUL ART WEEK

ART

WORDS BY GINEVRA BOSA

IN EARLY SEPTEMBER EVERY YEAR, SEOUL ERUPTS IN A CRESCENDO OF ART FAIRS, GALLERY OPENINGS, CURATED PARTIES, AND A FLURRY OF ONLINE PUBLICATIONS PROPOSING ENDLESS ITINERARIES FOR THE DISCERNING ART-GOER. THERE WERE THE BLUE-CHIP BOOTHS OF FRIEZE (WHICH HAS ESTABLISHED A PRESENCE IN SEOUL SINCE 2022), THE EARNEST SPECULATION OF KIAF (THE MAJOR KOREAN ART FAIR SINCE 2002), AND THE KALEIDOSCOPE OF SATELLITE SHOWS AND POP-UP OPENINGS ORBITING THE TWO. BY MIDWEEK, YOU COULD BARELY KEEP TRACK OF WHICH NEON-LIT BASEMENT OR GLASSY ROOFTOP YOU WERE MEANT TO BE IN NEXT. SEOUL ART WEEK HAD REACHED FULL VELOCITY, NOT UNLIKE THE CITY ITSELF – ENDLESSLY LAYERED, PERCUSSIVE, SLIGHTLY ELUSIVE.

But amidst the din of art-world programming, another rhythm began to surface – not just visual, but sonic. If Seoul Art Week felt like a chorus of competing voices, I started to wonder: What exactly do we hear – and miss – when art tries to speak across cultures? How do we navigate art that emerges from different visual idioms, historical references, and linguistic traditions? Can we truly listen, or are we merely projecting our own assumptions onto the noise? This wasn’t simply a question of language (though language would play a part). It was a question of signal: What cuts through the globalised hum of the art market? What becomes distorted in translation? And how might silence itself carry a form of intelligence – even resistance? It was here that I found myself returning to sound – not literally, but as a metaphor. These auditory concepts – noise, signal, silence – became my framework for tuning into the week. What began as a playful lens soon evolved into a method of perception, helping me differentiate between surface spectacle, clear artistic intent, and the eloquence of what remains unspoken. It was with this in mind that I moved, over the week, between the gallery districts of Hannam and Samcheong, the glaring hallways of the main fairs, and a series of exhibitions – particularly by artists Etsu Egami, Hansaem Kim, and Heryun Kim – whose work invited me into deeper reflections on language, miscommunication, and the possibility of listening through silence.

NOISE: THE SURFACE BUZZ

Seoul Art Week crackled with aesthetic signals – so many, in fact, that it became hard at times to parse what was truly meaningful and what was simply repetition. At Frieze and Kiaf, the air buzzed with overlapping voices: collectors negotiating over canvases, advisors on phone calls, fairgoers snapping photos for social media, gallerists volleying between Korean and English with crisp efficiency. Some booths hosted impromptu walkthroughs, others staged quick press interviews or echoed with the clink of glasses. It was a soundscape of speculation, performance, and commerce.

At the Tang Contemporary gala on Friday, a mix of collectors, curators, and local celebrities nursed champagne beneath high ceilings and warm lights. The room was charming, the energy high, and the works on view a carefully orchestrated spectacle. A striking painting by Etsu Egami hanging by the entrance became a focal point of conversation – not because of what it said, but because of the stir it caused.

There was buzz, certainly. But Egami’s work itself spoke in a very different register. She was showing at both major fairs – with Tang Contemporary at Frieze and Galerie Kornfeld at Kiaf – and it was at the latter that her painting Stunning Beauty – Fish Sink Into the Water and So Do Geese That Fly Through the Sky, Out of Shame Because of Beauty (2024) particularly drew my attention. It’s a mouthful of a title, but the canvas itself speaks through a layered bilinguality: on the left, calligraphy by her father – a Chinese poem invoking the legendary Four Beauties – and on the right, her signature diffused figuration, a fish rendered in the hues of water and memory.

At first glance, the work is beautiful. But look longer, and it becomes slightly unsettling – the poem refers to beauty so intense it causes fish to drown and geese to plummet from the sky. The fish Egami paints seem caught in that moment: not swimming but sinking.

Egami’s practice is deeply rooted in the fragility and fluidity of language. Her work explores the gaps where speech fails and meanings diverge. When we spoke, she referenced Jacques Derrida’s idea of différance, the slippage of meaning not just between languages, but within them. She explained this through an anecdote: ‘You can understand all the words in a sentence,’ she told me, ‘but still not grasp the joke – the cultural reference, the irony, the mood. Language is never just words.’

Growing up between Tokyo, Paris and Washington D.C., Egami experienced firsthand the friction of cultural misalignment. Later, while studying in Germany and Beijing, she became fascinated by misheard conversations. ‘I began painting from memory – not what was said, but what was misunderstood.’ Her paintings are often collaborations, blurring her own mark with others’: her father’s hand, or that of a translator. Misunderstanding is not a failure in Egami’s work – it’s a method.

That same day, back at Kiaf, I overheard a collector dismiss a painting as ‘too trendy’ and another call a work ‘a good investment if you’re betting on Korean abstraction’. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this transactional buzz – it’s part of the fair ecosystem. But standing in front of Egami’s painting, which quietly resists resolution while masquerading as harmony, I wondered: what else was slipping past us in the noise?

In a similar register of spectacle and speculative futures, Lee Bul’s retrospective Lee Bul: From 1998 to Now at the Leeum Museum of Art offered a different kind of sensory overload. Her Civitas Solis series unfolded through the galleries with science-fiction echoes, utopian architecture, and the suggestion of ruin. Mirrored surfaces collided with fractured edges; glass shards and reflective panels refracted both gallery light and spectators themselves. The installation felt like a city on the brink: brilliant, aspirational, precarious.

Lee’s work, always hovering between monument and malfunction, felt like an echo chamber of modernity’s promises. There was visual noise – texture, reflection, distortion – not just spectacle, but substance. Her compositions mirror the fragile foundations of our own techno-futures. The intensity wasn’t superficial; it was a sonic boom of history colliding with the future – one that left a reverberating hum in your bones.

SIGNAL: WHAT CUTS THROUGH

Some works during Seoul Art Week transmitted like sonar – quiet, pulsing, and precise. One such exhibition was Hansaem Kim’s NOWON at ThisWeekendRoom, which I noticed while passing by during Hannam’s Tuesday night gallery cluster. Through the glass, I caught sight of small, peculiar works that fused gothic religious motifs with the pixelated aesthetics of old computer graphics – enough to pull me inside.

In the basement, projected on the wall was Cut and Burn (2025), an 8-bit video game Hansaem Kim developed using the pixelated grammar of early console aesthetics. The work is simple in form but rich in metaphor: the player wanders through a haunted simulation of Nowon, the district where Kim currently lives, encountering small structures, ghostly figures, and half-erased signs. At moments, the game world itself seems unstable – part nostalgia, part distortion, part hallucination.

Nowon, Kim explained, also plays with homonyms – phonetically close to ‘no one’ – hinting at a sense of erasure and dispossession. The title suggests cycles of repetition without resolution, a city constantly rebuilding itself atop its own ruins.

Surrounding the projection were sculptural works: digitally designed and then hand-weathered objects in insulation foam, plastic roofing, and corrugated materials. They felt like material residues of a disappeared city, or perhaps a city always being overwritten.

In our conversation, Kim spoke about ‘zones of erasure’, not just in urban space but in memory. ‘We think architecture preserves history, but often it just replaces it. And language works the same way – replacing the real with representation.’ His game isn’t about winning or completing a task. It’s about wandering through a language you no longer fully speak.

Another work that crackled with frequency – both literal and conceptual – was Listening Guests by Kim YoungEun, part of the Korea Artist Prize 2025 exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA). Unlike her other works on surveillance or wartime acoustics, Listening Guests is gentle in tone yet radical in implication. The video installation overlaps the lives of Soviet Korean migrants in South Korea with those of Korean-American immigrants in Los Angeles. Sound here is not ambience – it’s agency. We hear overlapping testimonies about hearing one’s mother tongue in a foreign city, or not understanding the sound of home when heard out of context. As the artist notes, for diasporic communities, sound is more than hearing – it’s an act of survival.

That tension between recognition and distortion reverberated across several works I encountered during the week. Whether through Egami’s blurred bilingualisms, Kim YoungEun’s layered testimonies, or Hansaem Kim’s glitching urban landscapes, these artists don’t attempt to resolve dissonance. Instead, they ask us to dwell in it – to listen through it. What they offer is not neat clarity, but attunement.

SILENCE: THE SPACE BETWEEN

On Thursday, Samcheong night unfolded like a street party. Kukje Gallery hosted free drinks in the adjacent square, and three exhibitions were running inside. Crowds spilled into the street – a mix of art students, seasoned curators, and the occasional influencer posing near a sculpture. The mood was festive, even theatrical, and the city itself seemed to be performing – streets became runways, courtyards stages.

After this exuberance, the following morning offered a moment of stillness – the kind that recalibrates your senses – when I visited Heryun Kim’s show at Wooson Gallery. The gallery was empty, but the true silence emanated from the works themselves. Titled Sound of Silence, the exhibition unfolded in two parts – one in Seoul (Sound of Silence: Painting Forest), the other in Daegu (Sound of Silence: Language of Stars) – and seemed less a statement than an atmosphere.

One painting in particular, Sound of Silence No.87 (2024), pulled me in. A large canvas rendered in deep blues and streaks of umber, it offered no clear figures, no narrative entry point – only a composition that felt like breath.

Heryun Kim’s works, at first glance abstract, are deeply rooted in the rhythms of language and landscape. But not language as code – language as atmosphere. She draws inspiration from traditional Korean poetics, where landscape becomes metaphor and silence a space for reflection.

In our exchange, she described her process as ‘tuning into the world’s pauses’. For her, silence is not mere absence but, as she put it, ‘the true breath of nature and art’ – a condition that dissolves boundaries between the senses.

The installation at Wooson bore this out. In one room, a soft sculptural arrangement evoked a quiet ritual space – not religious, exactly, but contemplative. Elsewhere, sound was suggested but never present, like a conversation held in another room.

It struck me that in contrast to the buzz of fairs, the bold declarations of some exhibitions, or even the emotive pull of diaspora narratives, Heryun Kim’s work offered something rare: not a signal, but a resonant void. Silence, in her vocabulary, was not a lack but a shape.

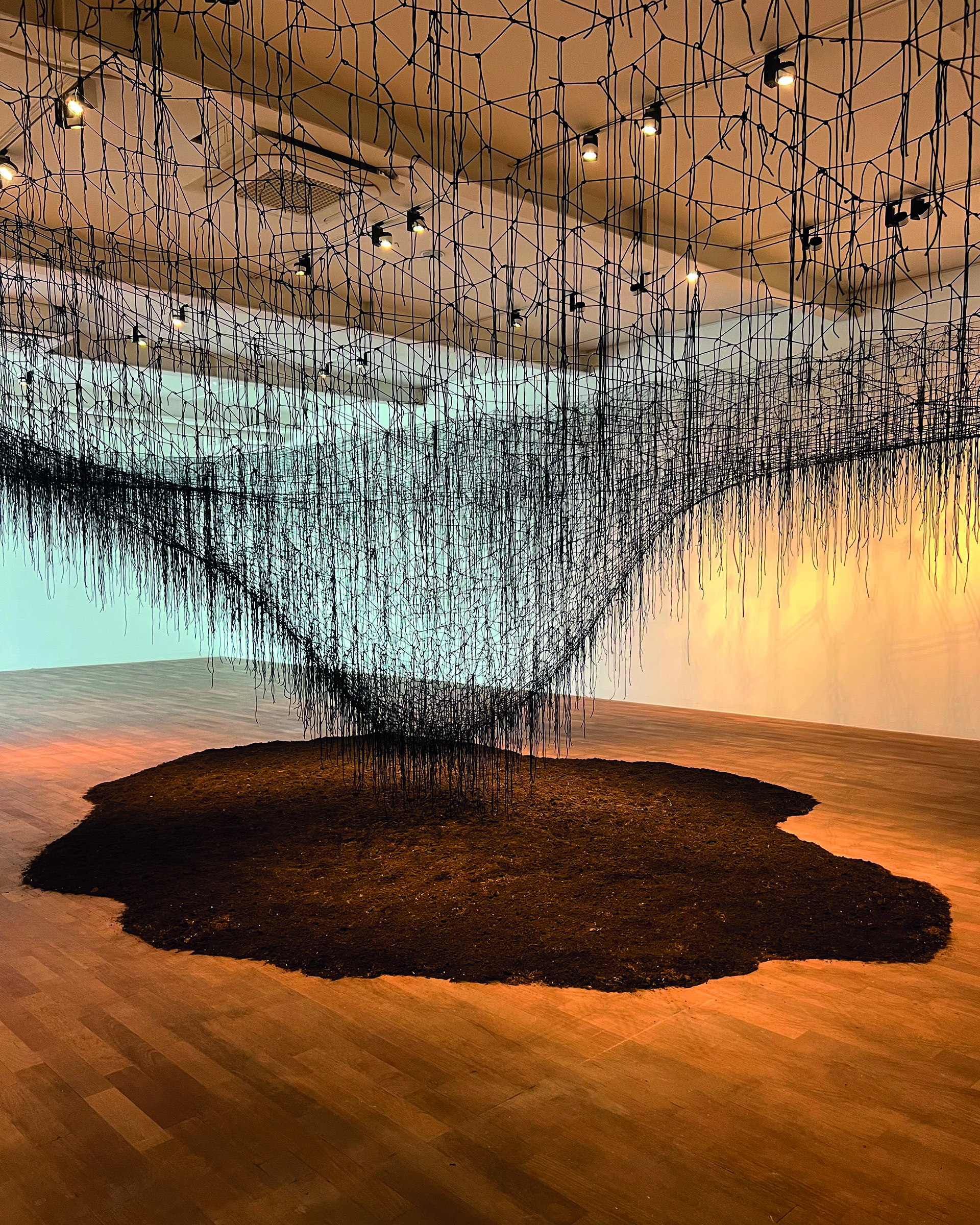

Meanwhile, at Gana Art Center, Shiota Chiharu unveiled Return to Earth – a solo exhibition that departed from her better-known red-thread installations in favour of quieter, more elemental works. Earth, wood, glass, and metal framed much of the display, evoking cycles of burial and renewal, memory and disappearance. Her sculptures felt like reliquaries – containers of unspoken grief.

In one room, the installation Endless Line traced delicate paths through space with black thread. These lines led neither to narrative nor resolution – only to a kind of spatial resonance, like faint trails from another time. Shiota has written that her works often begin with questions rather than answers. And in Return to Earth, the questioning is quiet, almost subterranean, but persistent.

Like Heryun Kim’s paintings, Return to Earth resisted the declarative. Both artists offered silence not as absence, but as density – a space that holds grief, memory, and meaning beyond language. If signal insists on being heard, silence demands to be felt.

CODA: LISTENING AS METHOD

Looking back at the week and beyond – the chatter at the fairs, the performances, the queue for wine at Kukje Gallery, the laughter in Samcheong, the strange poignancy of watching someone livestream an opening to their followers – I realise the art that stayed with me wasn’t necessarily the loudest. It was Etsu Egami’s blurred portraits borne from miscommunication, whose surface beauty concealed conceptual fault lines. It was Hansaem Kim’s haunted video game, quietly mapping urban memory as an unreadable code.

It was the sonic testimonies of Kim YoungEun’s migrants, tuning their ears to belonging. It was Shiota Chiharu’s tender traces, speaking of what vanishes. It was Heryun Kim’s eloquent silences, each brushstroke a breath withheld. And it was Lee Bul’s fractured futures, dazzling and broken in equal measure.

The noise / signal / silence framework, which began as a way to organise my impressions, has become something else: a way of listening. Not to what the art says outright, but to what it hesitates to speak. In a moment when much of contemporary art is pushed towards the declarative – statement-based, identity-forward, increasingly algorithm-friendly – it’s refreshing, even radical, to encounter work that opts instead for the ambiguous, the relational, the inaudible.

So perhaps the most interesting question coming out of Seoul Art Week isn’t what sold, or who showed where. Perhaps it’s a question that lingers: What are you hearing – and what are you missing?

NOISE, SIGNAL, SILENCE:

THE UNSPOKEN LANGUAGE OF SEOUL ART WEEK

Seoul Art Week from September 1 to 7

Tang Contemporary

Galerie Kornfeld, Leeum Museum of Art

ThisWeekendRoom

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA)

Kukje Gallery

Wooson Gallery

Gana Art Center

WORDS BY GINEVRA BOSA