From Ash to Tide

In Conversation with Rida Abdallah

INTERVIEW BY ELENA CESCON

L’ARTISTE FRANCO-LIBANAIS RIDA ABDALLAH, FORMÉ AUX BEAUX-ARTS DE PARIS ET DÉSORMAIS INSTALLÉ DANS LA BANLIEUE PARISIENNE, NAVIGUE DANS LA TENSION DÉLICATE ENTRE TRAGÉDIE ET BEAUTÉ, CAPTURANT UNE RÉALITÉ FRACTURÉE ET PROFONDÉMENT HUMAINE.

SA VISION CYCLIQUE DE LA VIE RÉVÈLE COMMENT CHAQUE GESTE RÉSONNE AVEC L’UNIVERS : INTIME OU MONUMENTAL, PERSONNEL OU UNIVERSEL. LE TRAVAIL DE RIDA OSCILLE ENTRE DÉSESPOIR ET ESPOIR, DESTRUCTION ET RENOUVEAU. AU FIL DE NOTRE ÉCHANGE, NOUS SOMMES INVITÉS À EXPLORER L’INTIMITÉ DU SOI ET LES RÉSONANCES DE L’EXPÉRIENCE HUMAINE, DÉVOILANT LES STRATES MULTIPLES DE SA PRATIQUE ÉVOCATRICE.

Franco-Lebanese artist Rida Abdallah, trained at the Beaux-Arts de Paris and now based in the Parisian banlieue, navigates the delicate tension between tragedy and beauty, capturing a fractured yet deeply human reality. His cyclical vision of life reveals how every gesture resonates with the universe: intimate or monumental, personal or collective. Rida’s work moves between despair and hope, destruction and renewal. As our conversation unfolds, we are invited to explore the intimacy of the self and the reverberations of human experience, uncovering the layered strata of his evocative practice.

NÉ À BEYROUTH, TU ARRIVES EN FRANCE AVEC TA MÈRE ET TA SŒUR À L’ÂGE DE 10 ANS. TU GRANDIS DANS UN ENVIRONNEMENT LITTÉRAIRE : TON PÈRE ÉTAIT POÈTE, TA MÈRE ET TA SŒUR SONT ROMANCIÈRES. DEVENIR ARTISTE ÉTAIT-IL UNE ÉVIDENCE OU TA FAMILLE ESPÉRAIT-ELLE QUE TU CHOISISSES UNE VOIE PLUS CLASSIQUE ?

Devenir artiste peintre n’était pas une évidence, surtout au Liban, où la littérature occupe une place centrale, bien plus reconnue, répandue et accessible que les arts visuels. La littérature y est une tradition profondément ancrée dans la culture, largement diffusée : même les personnes issues des classes populaires écrivent. Ma famille en est un reflet. Ma mère était professeure de français et écrivait aussi des articles et des nouvelles. C’est d’ailleurs grâce à son premier roman, rédigé au Liban et envoyé à un magazine arabophone à Londres, qu’elle a remporté un prix littéraire important et, par conséquent, une somme d’argent qui nous a permis de payer le voyage pour nous installer en France. Ma sœur a fait des études d’archéologie et son premier roman est paru suite au décès de mon père en 2019. Du côté de mon père, la littérature est encore plus présente, puisqu’il vient d’une famille connue pour avoir compté de nombreux poètes et journalistes. Au Liban, il est courant d’être à la fois journaliste et poète, ces deux pratiques étant étroitement liées. Ce sont des intellectuels qui ne viennent pas forcément de familles bourgeoises, mais bien souvent de milieux ruraux. Quant à moi, très jeune, on remarquait que je dessinais bien, mais j’avais surtout besoin de bouger et d’être à l’extérieur, loin du modèle de l’enfant studieux. J’entretenais d’ailleurs un rapport conflictuel avec l’école, ce qui rendait difficile un parcours académique classique. Le seul horizon possible fut alors les Beaux-Arts de Paris, où j’ai été admis après une année de préparation intense. Avant d’y entrer, je dessinais très peu, mais j’ai consacré un an à constituer mon dossier. Devenir artiste n’était donc pas une évidence, mais ma famille m’a soutenu, et c’est ma mère qui m’a encouragée à tenter l’examen d’entrée aux Beaux-Arts.

BORN IN BEIRUT, YOU MOVED TO FRANCE WITH YOUR MOTHER AND SISTER AT THE AGE OF 10. YOU GREW UP IN A LITERARY ENVIRONMENT: YOUR FATHER WAS A POET, AND YOUR MOTHER AND SISTER ARE NOVELISTS. WAS BECOMING AN ARTIST A NATURAL PATH FOR YOU, OR DID YOUR FAMILY HOPE YOU WOULD CHOOSE A MORE TRADITIONAL CAREER?

Becoming a painter was far from obvious, especially in Lebanon, where literature holds a central place, far more recognized, widespread, and accessible than the visual arts. Literature there, is a deeply rooted cultural tradition, widely practiced: even people from working-class backgrounds write. My family reflects this. My mother was a French teacher and also wrote articles and short stories. In fact, it was thanks to her first novel, written in Lebanon and sent to an Arab-language magazine in London, that she won an important literary prize and, consequently, received a sum of money that allowed us to cover the trip to settle in France. My sister studied archaeology, and her first novel was published following the death of my father in 2019. On my father’s side, literature was even more present, coming from a family known for producing numerous poets and journalists. In Lebanon, it’s common to be both a journalist and a poet, these practices are closely linked. These are intellectuals who don’t necessarily come from bourgeois families, but often from rural backgrounds. As for me, from a very young age, it was clear I could draw well, but I mostly needed to move around and be outside, far from the model of the studious child. I also had a complicated relationship with school, which made a traditional academic path difficult. The only possible horizon then became the Beaux-Arts de Paris, where I was admitted after an intense year of preparation. Before entering, I drew very little, but I spent a full year preparing my portfolio. Becoming an artist was therefore not a given, but my family supported me, and it was my mother who encouraged me to take the entrance exam at the Beaux-Arts.

TU AS BEAUCOUP TRAVAILLÉ AUTOUR DU THÈME D’UN MONDE QUI S’ÉCROULE : VILLES DÉTRUITES, SOCIÉTÉS EN RUINE, VIOLENCE ET CONFLITS. EST-CE UN SUJET QUI T’A TOUJOURS INSPIRÉ DANS TA CARRIÈRE OU Y A-T-IL EU UN MOMENT OU UN ÉVÉNEMENT PRÉCIS OÙ TU T’ES DIT : « IL FAUT QUE JE PARLE DE ÇA » ?

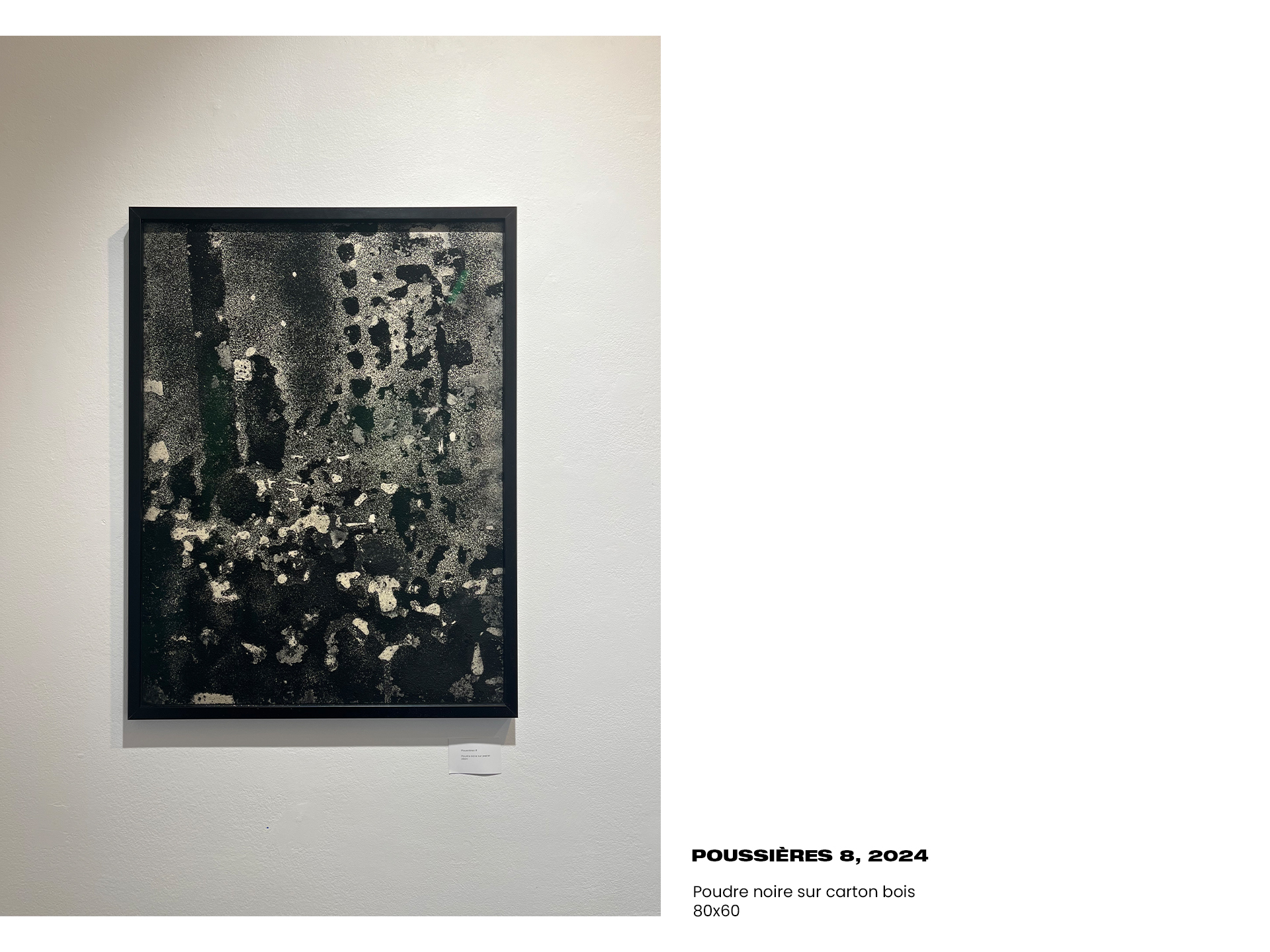

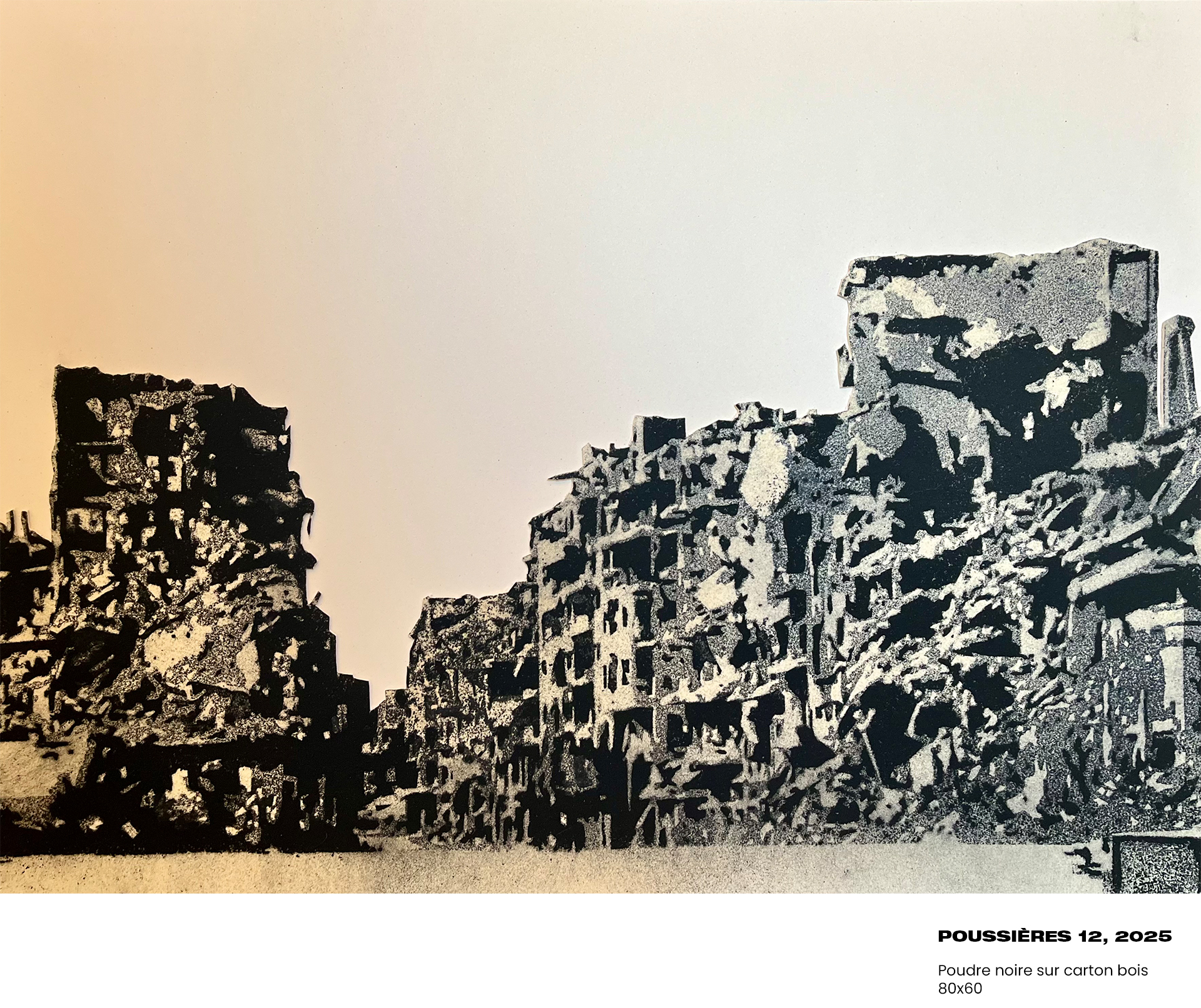

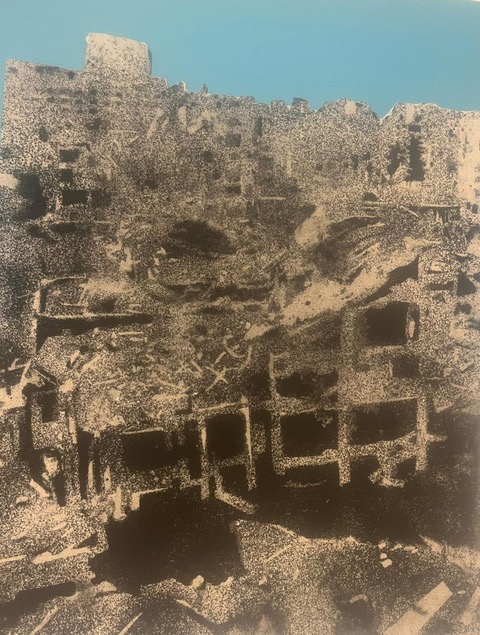

Au début de ma carrière, je travaillais surtout sur des scènes que l’histoire de l’art désigne comme des caprices : des compositions figuratives, peuplées de personnages énigmatiques, où l’on ne comprend qu’à moitié ce qui se passe. Une forme de semi-narration, laissant une large place à l’interprétation personnelle. Le thème des ruines et des villes en effondrement se trouve dans mon travail depuis désormais 3 ans, mais c’est un thème devenu vraiment central, il y a environ un an, à la Villa Empain, lorsque je travaillais à ma série Poussières. Avant la série Poussières, il y a eu la série Poudres, où j’ai commencé à tester la poudre noire et à traiter le thème des explosions, et avant cela il y a eu la série Pays, où les nuages avaient déjà commencé à se transformer progressivement en fumées. Mais disons que c’est à la Villa Empain, avec la série Poussières, que la narration et la pertinence du sujet sont devenues principales. Avant d’arriver à la Villa Empain, je travaillais beaucoup comme journaliste pour une chaîne d’information, ce qui m’avait éloigné du dessin et de la peinture. J’ai alors décidé de quitter définitivement le journalisme pour me consacrer entièrement à l’art, et la Villa Empain représentait pour moi l’occasion idéale de m’y engager pleinement. La résidence à la Villa Empain m’a obligé à choisir un sujet fort, sans perdre de temps. À cette période, j’étais imprégné des images des guerres avec lesquelles je travaillais en tant que journaliste, et il y circulait déjà les images de la guerre à Gaza. Quand je suis rentré à la Villa Empain, c’était aussi le début des bombardements de Beyrouth, que je me suis quand même forcé de ne pas trop regarder tout au long de ma résidence. C’est donc dans ce contexte que je me suis tourné vers le thème des ruines, travaillant parfois de manière presque obsessionnelle, jusque tard dans la nuit, dans les ateliers. C’est également à ce moment-là que j’ai commencé à travailler sérieusement la technique de la poudre, une technique que j’avais déjà commencé à explorer avec la série Poudres dans mon atelier en banlieue parisienne autour de 2023. À la Villa Empain, j’ai approfondi encore davantage cette approche.

YOU’VE WORKED EXTENSIVELY AROUND THE THEME OF A COLLAPSING WORLD: DESTROYED CITIES, SOCIETIES IN RUINS, VIOLENCE AND CONFLICT. HAS THIS ALWAYS BEEN A SOURCE OF INSPIRATION FOR YOU, OR WAS THERE A SPECIFIC MOMENT OR EVENT THAT MADE YOU SAY, “I NEED TO EXPLORE THIS”?

At the beginning of my career, I mostly worked on scenes that art history refers to as caprices: figurative compositions filled with enigmatic figures, where the narrative is only partially clear. It was a kind of semi-narrative, leaving ample room for personal interpretation. The theme of ruins and crumbling cities has been present in my work for about three years now, but it truly became central around a year ago, during my residency at Villa Empain, when I was working on my Poussières series. Before Poussières, there was the Poudres series, where I began experimenting with black powder and exploring explosions, and prior to that, the Pays series, in which clouds had already started to gradually transform into smoke. But it was at Villa Empain, with Poussières, that the narrative and the relevance of the subject truly took center stage. Before arriving at Villa Empain, I had been working extensively as a journalist for a news channel, which had pulled me away from drawing and painting. I decided to leave journalism entirely to devote myself fully to art, and the Villa Empain residency offered the perfect opportunity to commit completely. The residency at Villa Empain forced me to choose a strong subject, without wasting time. At that moment, I was saturated with images of wars I had covered as a journalist, and the visuals of the war in Gaza were already circulating. When I arrived at Villa Empain, it was also the beginning of the bombings in Beirut, which I deliberately tried not to follow too closely throughout my residency. It was in this context that I turned to the theme of ruins, sometimes working almost obsessively, late into the night, in the studio. It was also at this time that I began working seriously with the powder technique, which I had already started exploring in the Poudres series in my suburban Paris studio around 2023. At Villa Empain, I deepened this approach even further.

TU ES UN « ENFANT DE LA GUERRE DU LIBAN ». POURTANT, TU NE TRAITES PAS DIRECTEMENT CE SUJET, TU L’ÉLARGIS À TOUTES LES VILLES, TOUS LES CONFLITS, TOUS LES PEUPLES. Y A-T-IL MALGRÉ TOUT TOUJOURS UNE PETITE TACHE DANS TES ŒUVRES QUI PARLE DE BEYROUTH ?

Oui, il y a toujours une tâche de Beyrouth dans mes œuvres, et elle n’est pas petite : elle est immense. Mais comme elle est immense, elle est douce, diffuse, presque invisible. Je ne la représente jamais de manière précise, comme une carte ou un repère identifiable. Elle fait partie de moi, elle est sous-jacente, latente. Il y a un verbe français que j’aime beaucoup : sourdre, comme l’eau qui jaillit doucement de la terre. C’est exactement ce que représente Beyrouth dans mon travail : un flux discret mais constant. Et, plus généralement, le choix de ne pas donner de titre ou de visage particulier aux villes me permet de ne pas tomber dans le détail et dans sa propre anecdote, car pour moi, plus on se rapproche d’une chose, moins on la voit. Et paradoxalement, s’il y a une chose que le particulier nous apprend, c’est que le particulier n’existe pas. Cette distance m’aide à ne pas me limiter à ma propre histoire, mais à m’ouvrir à celles des autres. Une volonté de mon travail à ce sujet est aussi de montrer que toutes les villes s’écroulent de la même manière : elles perdent leur identité lorsqu’elles subissent le malheur, et c’est cette universalité qui m’intéresse. Comme le disait Jacques Brel : « Tout le monde a mal aux dents de la même façon. » Cette idée d’expérience partagée est fascinante, à la fois humainement et artistiquement. Toujours Jacques Brel disait une fois : « J’ai mal aux autres. » Parallèlement, mon travail est aussi une manière d’exorciser mes sentiments et mes souvenirs, de ne pas les laisser devenir des poids ou des démons. En créant des sujets impersonnels, je dilue ma propre histoire dans l’encre et la peinture. C’est comme une chanson triste qui, paradoxalement, devient agréable à écouter : elle parle de tristesse mais la transforme en beauté. L’art permet ainsi d’éclairer le passé et de projeter de la lumière vers l’avenir.

YOU MIGHT BE CONSIDERED A “CHILD OF THE LEBANESE WAR.” YET YOU DON’T ADDRESS THE SUBJECT DIRECTLY, INSTEAD EXPANDING IT TO ALL CITIES, ALL CONFLICTS, ALL PEOPLES. STILL, IS THERE ALWAYS A TRACE IN YOUR WORK THAT SPEAKS OF BEIRUT?

Yes, there is always a trace of Beirut in my work, and it’s not small: it’s immense. But because it is so vast, it is gentle, diffuse, almost invisible. I never depict it in a literal way, like a map or an identifiable landmark. It is part of me; it lies beneath the surface, latent. There’s a French verb I love: sourdre like water gently springing from the earth. That is exactly what Beirut represents in my work: a subtle but constant flow. More broadly, choosing not to give specific titles or recognizable faces to the cities allows me to avoid getting caught in details or personal anecdotes. For me, the closer you look at something, the less you see. Paradoxically, one thing the particular teaches us is that the particular doesn’t really exist. This distance helps me move beyond my own story and open up to others’ experiences. Part of my aim is also to show that all cities collapse in the same way: they lose their identity when they endure misfortune, and it’s this universality that interests me. As Jacques Brel once said: “Everyone has toothache in the same way.” This idea of shared experience is fascinating, both humanly and artistically. Brel also said: “I feel the pain of others.” At the same time, my work serves as a way to exorcise my own feelings and memories, to prevent them from becoming burdens or demons. By creating impersonal subjects, I dilute my personal history into ink and paint. It’s like a sad song that, paradoxically, becomes pleasant to listen to: it expresses sorrow while transforming it into beauty. Art allows us to illuminate the past and cast light toward the future.

POUSSIÈRES 9, Poudre noire sur carton bois, 80×60, 2024

DANS POUSSIÈRES, D’OÙ T’INSPIRES-TU POUR TES REPRÉSENTATIONS ? DES IMAGES JOURNALISTIQUES, D’AUTRES ARTISTES, DES PHOTOS QUE TU PRENDS TOI-MÊME, OU BIEN DE SOUVENIRS PERSONNELS ? VOYAGES-TU PARFOIS POUR ALLER À LA RENCONTRE DE RUINES, UN PEU COMME UN « ARCHÉOLOGUE DU PRÉSENT » ?

Je ne voyage pas expressément pour aller à la rencontre de ruines, même si je retourne souvent à Beyrouth. En général, il me suffit de fermer les yeux pour me déplacer dans l’espace. Les images télévisées et les photographies que je prends moi-même nourrissent mon regard, mais je m’inspire aussi énormément des travaux des autres, notamment dans le rapport aux textures. J’essaie toujours d’explorer de nouveaux médiums, de nouvelles matières : c’est une recherche permanente. Pour Poussières, j’ai souvent pensé aux travaux et aux artistes de la vieille photographie et de la straight photography américaine, qui avaient, dans le processus et le langage, beaucoup de liens avec mon initiative, notamment Gustave Le Gray, Eugène Atget, Walker Evans et l’école de Düsseldorf. Le sujet de la destruction a longtemps été central, mais je sens déjà qu’il évolue. Mes prochaines recherches ne seront pas très éloignées des ruines, mais davantage liées au minéral, à la matière profonde. Le terme « archéologue du présent » me paraît juste, mais j’oserais aller plus loin : ce que je fais s’apparente tout autant à une forme de spéléologie. J’ai beaucoup pratiqué cette discipline, notamment dans les catacombes parisiennes. Elle m’a marqué par cette idée de strates, de couches qui s’accumulent les unes sur les autres, comme un palimpseste du temps. Passé, présent et futur s’y entremêlent dans une continuité cyclique : des acteurs se meuvent entre deux mondes parallèles superposés qui s’ignorent, en plein jour et dans les ténèbres. C’est ainsi que je perçois aussi l’histoire humaine : un cycle immuable, comme celui des plaques tectoniques qui avancent, reculent, se heurtent, créant tantôt une montagne, tantôt un séisme. La violence, les guerres, les conflits répondent à ce même mouvement éternel. Mon travail s’attache à explorer cette stratification, dans la matière comme dans l’histoire. C’est une fouille, intime et universelle à la fois, qui tente de rendre visible ce qui se répète, ce qui persiste et ce qui continue de sourdre dans nos mémoires collectives.

WHERE DO YOU DRAW YOUR INSPIRATION FROM? JOURNALISTIC IMAGES, OTHER ARTISTS, PHOTOGRAPHS YOU TAKE YOURSELF, OR PERSONAL MEMORIES? DO YOU SOMETIMES TRAVEL TO ENCOUNTER RUINS, ALMOST LIKE A “PRESENT-DAY ARCHAEOLOGIST”?

I don’t travel specifically to seek out ruins, although I do return to Beirut often. Usually, it’s enough for me to close my eyes to move through space. Television images and photographs I take myself feed my vision, but I also draw a great deal of inspiration from the work of other artists, especially in their use of texture. I’m always trying to explore new mediums, new materials, it’s a constant process of experimentation. For Poussières, I often thought about the work of early photographers and the American straight photography movement, whose processes and visual language share much in common with my own approach, artists like Gustave Le Gray, Eugène Atget, Walker Evans, and the Düsseldorf School. The theme of destruction has long been central to my work, but I already feel it evolving. My upcoming projects won’t stray far from ruins, but they will focus more on mineral forms and the essence of matter itself. The term “present-day archaeologist” feels accurate, but I would even go further: what I do also resembles a form of caving or spelunking. I’ve practiced this extensively, especially in the Paris catacombs. That experience left a deep impression on me, particularly the concept of strata-layers building upon layers, like a palimpsest of time. Past, present, and future intertwine in a cyclical continuity, with actors moving between two overlapping parallel worlds that remain unaware of each other, in daylight and in darkness. This is also how I perceive human history: an unchanging cycle, like tectonic plates shifting, colliding, sometimes forming mountains, sometimes causing earthquakes. Violence, wars, and conflicts follow the same eternal rhythm. My work seeks to explore this layering, both in material and in history. It is an excavation, at once intimate and universal, attempting to make visible what repeats, what endures, and what continues to sourdre – to quietly rise – in our collective memory.

TA TOILE PAYS 4 (ACRYLIQUE ET ENCRE) A FAIT LA UNE DE L’HUMANITÉ EN OCTOBRE 2024, MARQUANT UN TOURNANT DE VISIBILITÉ. UN AN APRÈS, QUE REPRÉSENTE POUR TOI CETTE ŒUVRE ?

Une précision importante : Pays 4 a été réalisée deux ans avant sa publication dans L’Humanité, pour la une de son édition du 28 octobre, moment où les bombardements à Beyrouth ont commencé et où je venais d’arriver à la Villa Empain. À cette époque, le danseur et chorégraphe libanais Ali Chahrour s’intéressait particulièrement à mes œuvres. Je travaillais alors sur ma série Poussières, et c’est lui qui a présenté mon travail au journal. C’est ainsi que Pays 4, une œuvre antérieure, a été choisie pour illustrer la une du numéro. Pour moi, Pays 4 représentait une ville anonyme, sans nom précis. Mais elle avait effectivement été inspirée par une image vue dans un reportage sur Beyrouth. L’Humanité l’a utilisée pour accompagner un appel lancé par des artistes libanais réclamant l’arrêt des bombardements israéliens sur le Liban, donnant à cette image une portée symbolique inattendue et assez efficace. Souvent, surtout dans les pays arabes, on m’interroge sur le lien entre mon travail et les conflits du Moyen-Orient. Je précise toujours que mon approche est unilatérale : je ne cherche pas à politiser, mais à montrer la similarité des destructions. La violence touche toutes les villes, ici ou ailleurs, hier, aujourd’hui ou demain. Pour moi, le malheur est universel, et Pays 4 illustre cette continuité et cette essence partagée de la destruction. Toutes les villes s’écroulent de la même manière et deviennent à mes yeux la même ville. Ce n’est pas seulement des corps et des structures, mais une identité qu’on détruit, du minéral et un peu de viande. Aujourd’hui, un an plus tard, la une avec Pays 4 est encadrée et trône à côté de mon frigo, entre une photo de différents types de tomates et une photo de ma nièce Yasmine en train de manger un kebab.

YOUR PAINTING PAYS 4 (ACRYLIC AND INK) MADE THE FRONT PAGE OF L’HUMANITÉ IN OCTOBER 2024, MARKING A MAJOR MOMENT OF VISIBILITY. A YEAR LATER, WHAT DOES THIS WORK REPRESENT FOR YOU?

It’s important to clarify: Pays 4 was actually created two years before its appearance on the front page of L’Humanité, for the October 28 issue, the moment when the bombings in Beirut began and I had just arrived at Villa Empain. At that time, the Lebanese dancer and choreographer Ali Chahrour had a particular interest in my work. I was working on my Poussières series, and it was he who introduced my work to the newspaper. That’s how Pays 4, an earlier piece, was chosen to illustrate the front page. For me, Pays 4 depicted an anonymous city, without a specific name. Yet it was indeed inspired by an image I had seen in a report about Beirut. L’Humanité used it to accompany an appeal by Lebanese artists calling for an end to the Israeli bombings of Lebanon, giving the image an unexpected and quite powerful symbolic resonance. Often, especially in Arab countries, I’m asked about the connection between my work and Middle Eastern conflicts. I always clarify that my approach is unilateral: I don’t aim to politicize, but to highlight the similarity of destruction. Violence affects all cities: here or elsewhere, yesterday, today, or tomorrow. Misfortune is universal, and Pays 4 reflects this continuity and the shared essence of destruction. All cities collapse in the same way and, in my eyes, become the same city. It’s not just about bodies and structures, it’s an identity being destroyed, mineral matter and a bit of flesh. Today, a year later, the front page featuring Pays 4 is framed and sits next to my fridge, between a photo of different types of tomatoes and a photo of my niece Yasmine eating a kebab.

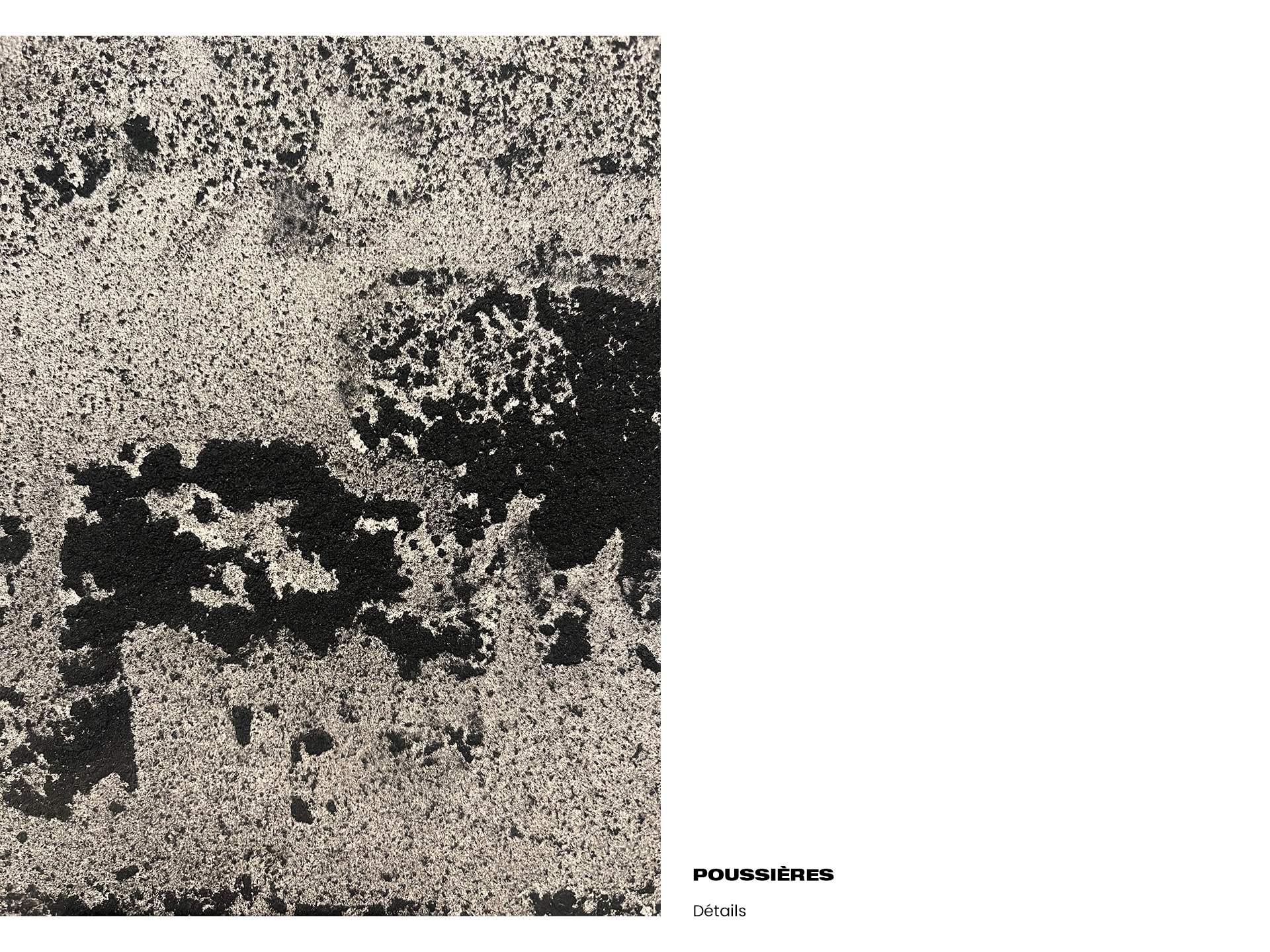

LORS DE TA RÉSIDENCE À LA VILLA EMPAIN, COMME MENTIONNÉ, TU AS TRAVAILLÉ SUR TA SÉRIE POUSSIÈRES, EN EXPÉRIMENTANT LE DESSIN À LA POUDRE NOIRE DE FUSAIN. CETTE MATIÈRE ÉVOQUE AUTANT LA CENDRE QUE LA POUDRE À CANON. QUELLE SYMBOLIQUE AS-TU VOULU Y METTRE ?

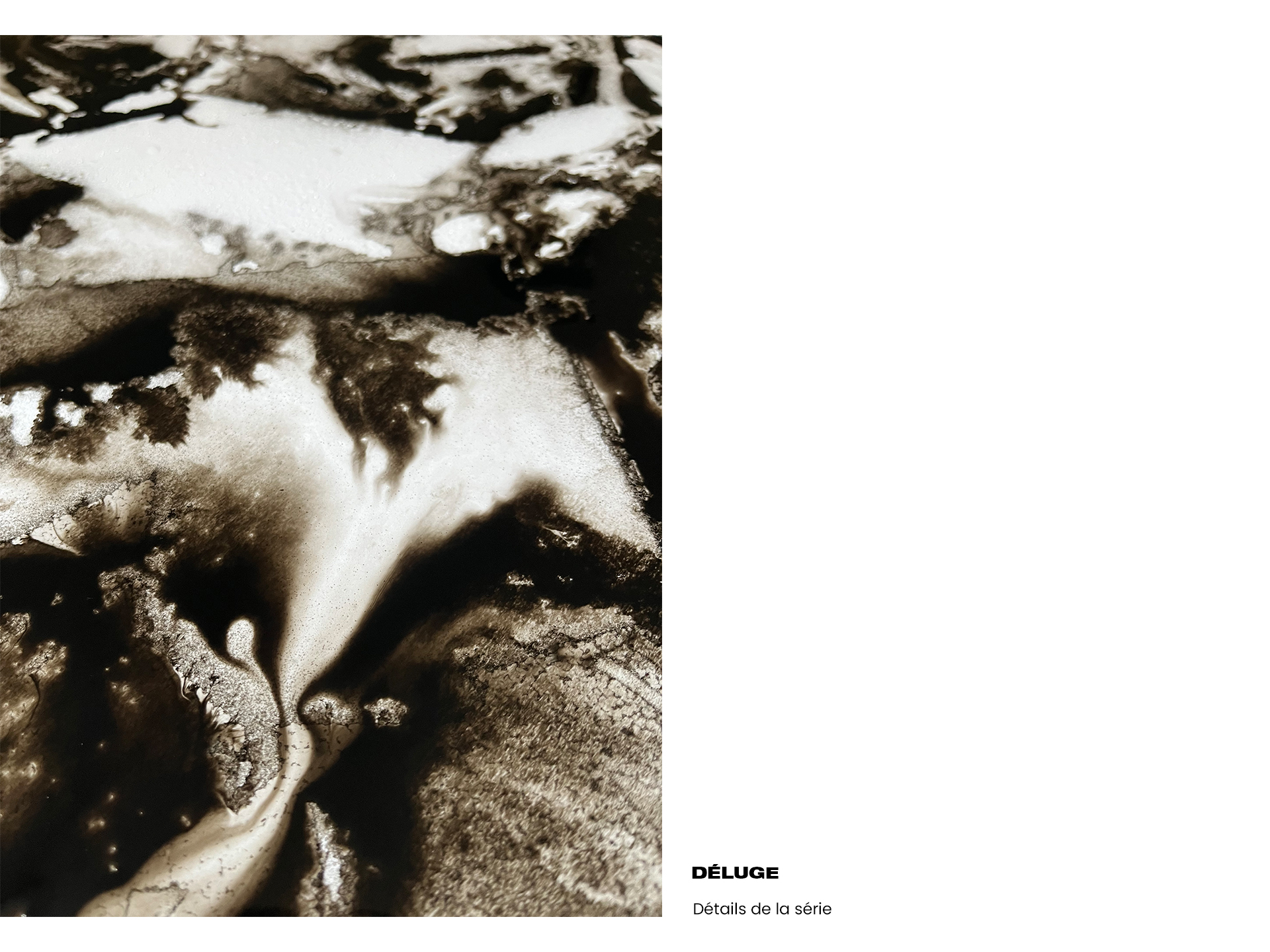

Il y a beaucoup de symboliques dans cette matière, et c’est justement ce qui m’intéresse. Comme tu l’as dit, il y a cette notion de cendre, de poudre à canon, qui évoque la destruction. Mais il y a aussi une dimension biblique : la phrase du Livre de la Genèse, après la chute d’Adam, « Memento, homo, quia pulvis es, et in pulverem reverteris », traduite du latin : « Souviens-toi, homme, que tu es poussière et que tu redeviendras poussière ». La poussière renvoie également à un état très primaire, presque minéral, atomique des choses. Et en même temps, elle représente presque rien, d’où l’expression « il ne reste que des poussières ». La technique elle-même porte aussi une symbolique : je laisse la poudre tomber sur le papier, comme un effet d’attraction terrestre inéluctable. C’est difficile à contrôler, et cela m’apprend à composer avec la réalité plutôt qu’à la transiger. Il y a aussi un aspect de fragilité très important, tant dans le sujet que dans les œuvres elles-mêmes. Ces pièces ont un côté lunaire et brûlé : certains produits chimiques que j’utilise, dans les zones où je cherche l’épaisseur, donnent un effet de charbon cristallisé, presque sculpté. Cette matière et ces effets invitent le spectateur à se rapprocher, à examiner les cratères et les textures, à s’immerger dans les détails. C’est un travail de minutie, c’est un silence d’après le fracas, qui engage autant l’artiste que le spectateur. On se confronte à la sophistication des formes, qui restent silencieuses, presque à l’opposé du discours journalistique, politique ou géopolitique. C’est un grand silence chargé de beaucoup de choses, un autre langage, un alphabet différent, et c’est précisément cela qui rend l’art fascinant.

DURING YOUR RESIDENCY AT VILLA EMPAIN, AS MENTIONED, YOU WORKED ON YOUR POUSSIÈRES SERIES, EXPERIMENTING WITH DRAWING IN BLACK CHARCOAL POWDER. THIS MATERIAL EVOKES BOTH ASH AND GUNPOWDER. WHAT SYMBOLISM DID YOU INTEND TO CONVEY THROUGH IT?

There are many layers of symbolism in this material, and that’s precisely what fascinates me. As you said, there’s the notion of ash and gunpowder, which naturally evokes destruction. But there’s also a biblical dimension: the phrase from the Book of Genesis, after Adam’s fall, “Memento, homo, quia pulvis es, et in pulverem reverteris”, which translates as: “Remember, man, that you are dust and to dust you shall return.” Dust also refers to a very primal, almost mineral and atomic state of things. At the same time, it represents almost nothing, which is captured in the expression, “all that remains are dust and ashes.” The technique itself carries symbolism: I let the powder fall onto the paper, like an inexorable force of gravity. It’s difficult to control, and it teaches me to work with reality rather than impose on it. There’s also a strong sense of fragility, both in the subject and in the works themselves. These pieces have a lunar, burnt quality: certain chemicals I use, in areas where I build up thickness, create a crystallized charcoal effect, almost sculptural. This material and these textures invite the viewer to come closer, to examine the craters and surfaces, to immerse themselves in the details. It’s meticulous work, a silence after the crash, engaging both the artist and the viewer. We confront the sophistication of the forms, which remain silent, almost in opposition to journalistic, political, or geopolitical discourse. It’s a profound silence, filled with meaning – another language, a different alphabet – and it’s precisely this that makes art so fascinating.

POUSSIÈRES 4, Poudre noire sur carton bois, 80×60, 2025

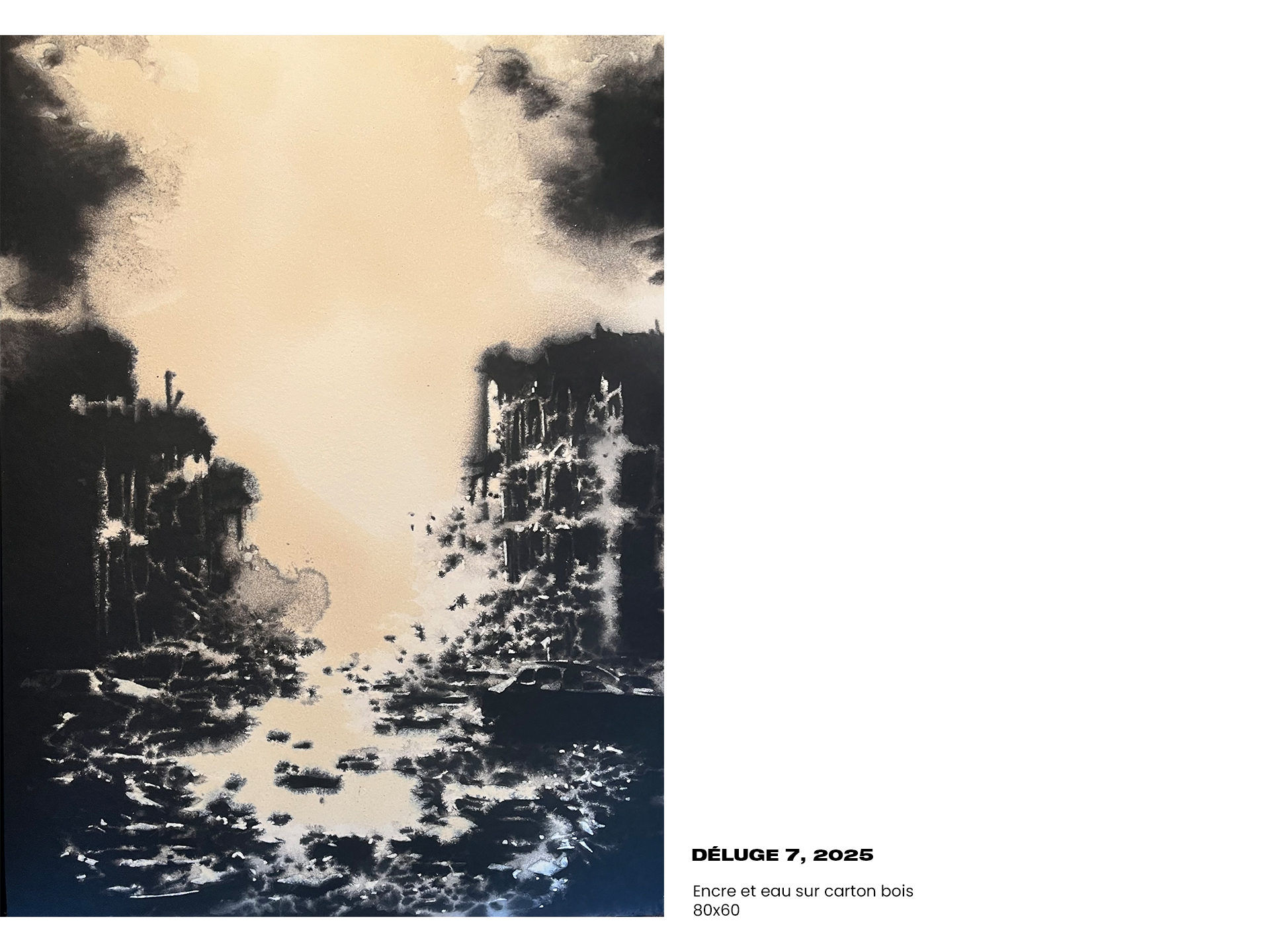

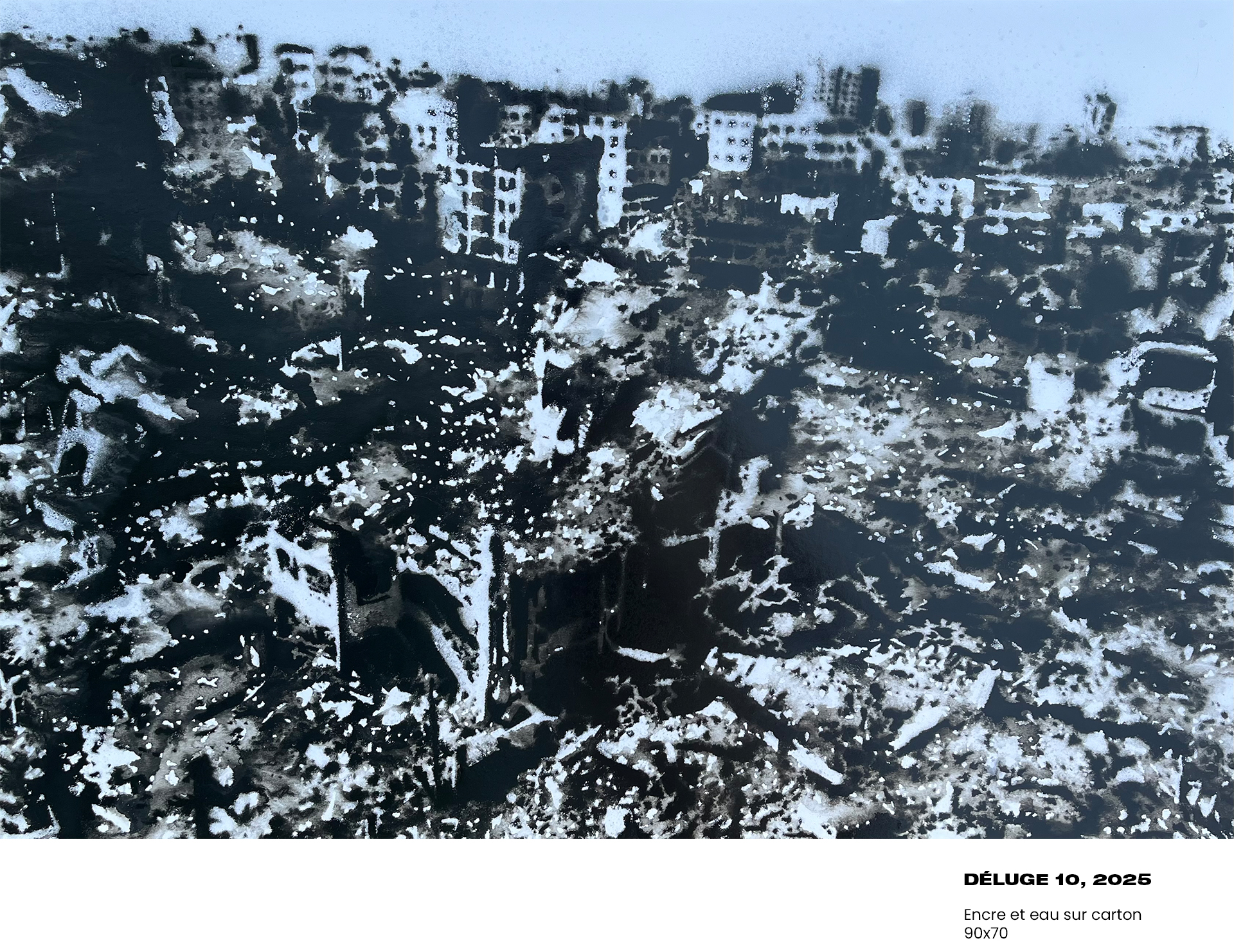

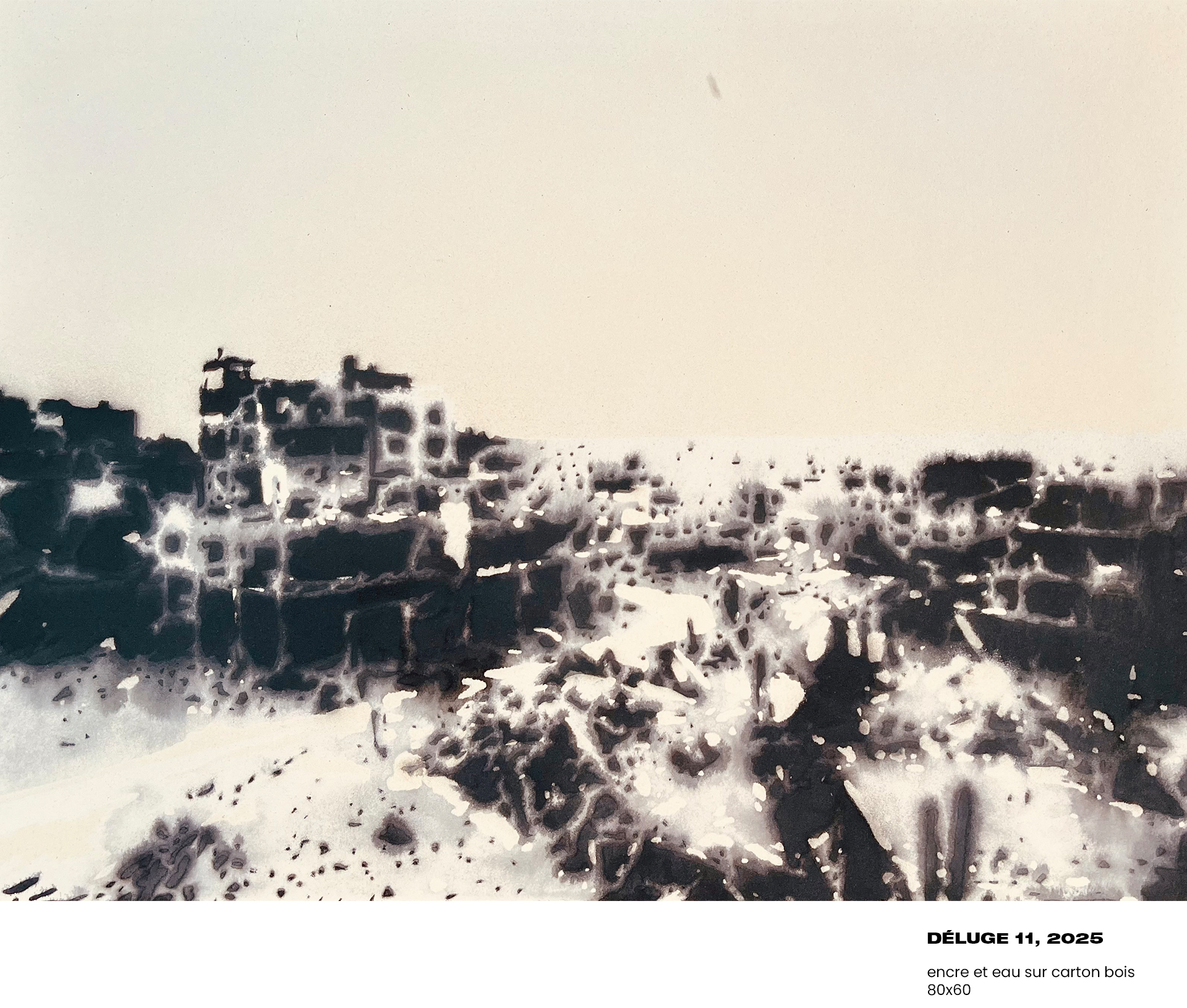

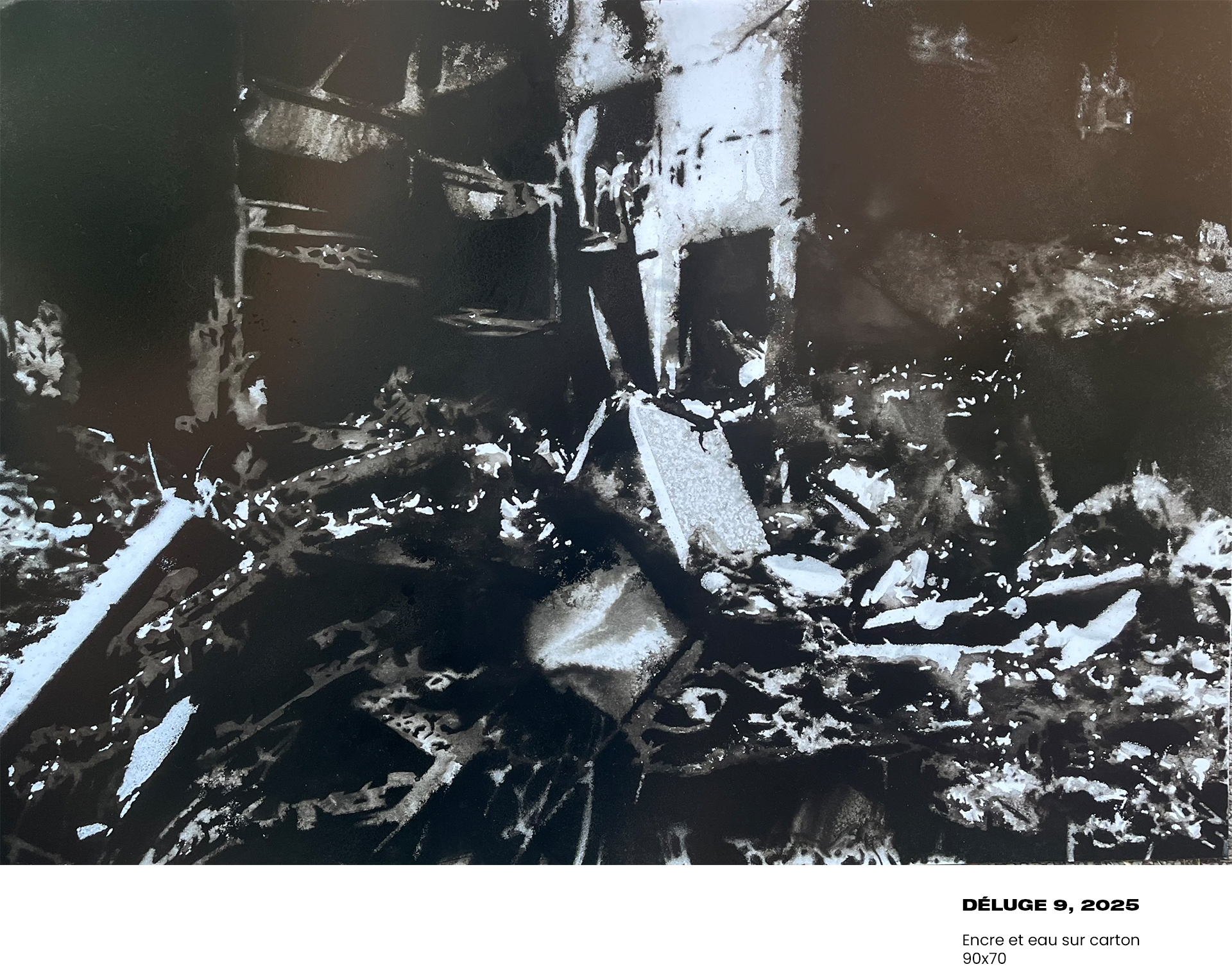

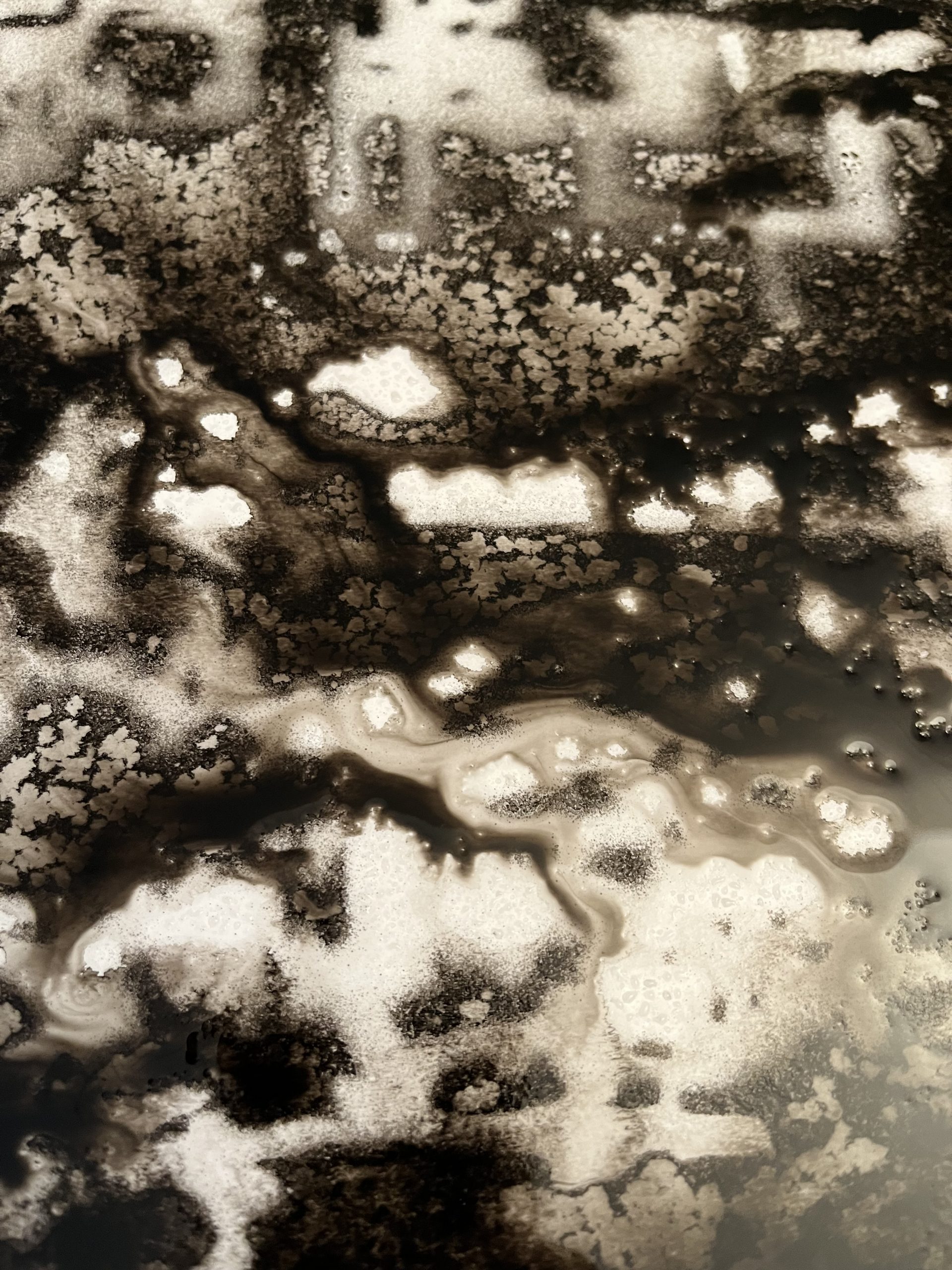

EN 2025, TU EXPLORES UNE NOUVELLE TECHNIQUE AVEC LA SÉRIE DÉLUGE, DESSINS À L’ENCRE ET À L’EAU SUR CARTON. CELA VIENT-IL D’UNE VOLONTÉ DE TOURNER LA PAGE POUR PASSER À UNE NOUVELLE NARRATION ?

D’un côté, la série Déluge reste une série de ruines et de destructions. Il est vrai que certaines scènes peuvent sembler aquatiques au premier regard, mais si l’on s’approche, on découvre des villes détruites par le feu, bombardées. Le même enjeu persiste, mais je joue entre deux éléments opposés : l’eau et le feu, et cette ambivalence traverse toute la série.

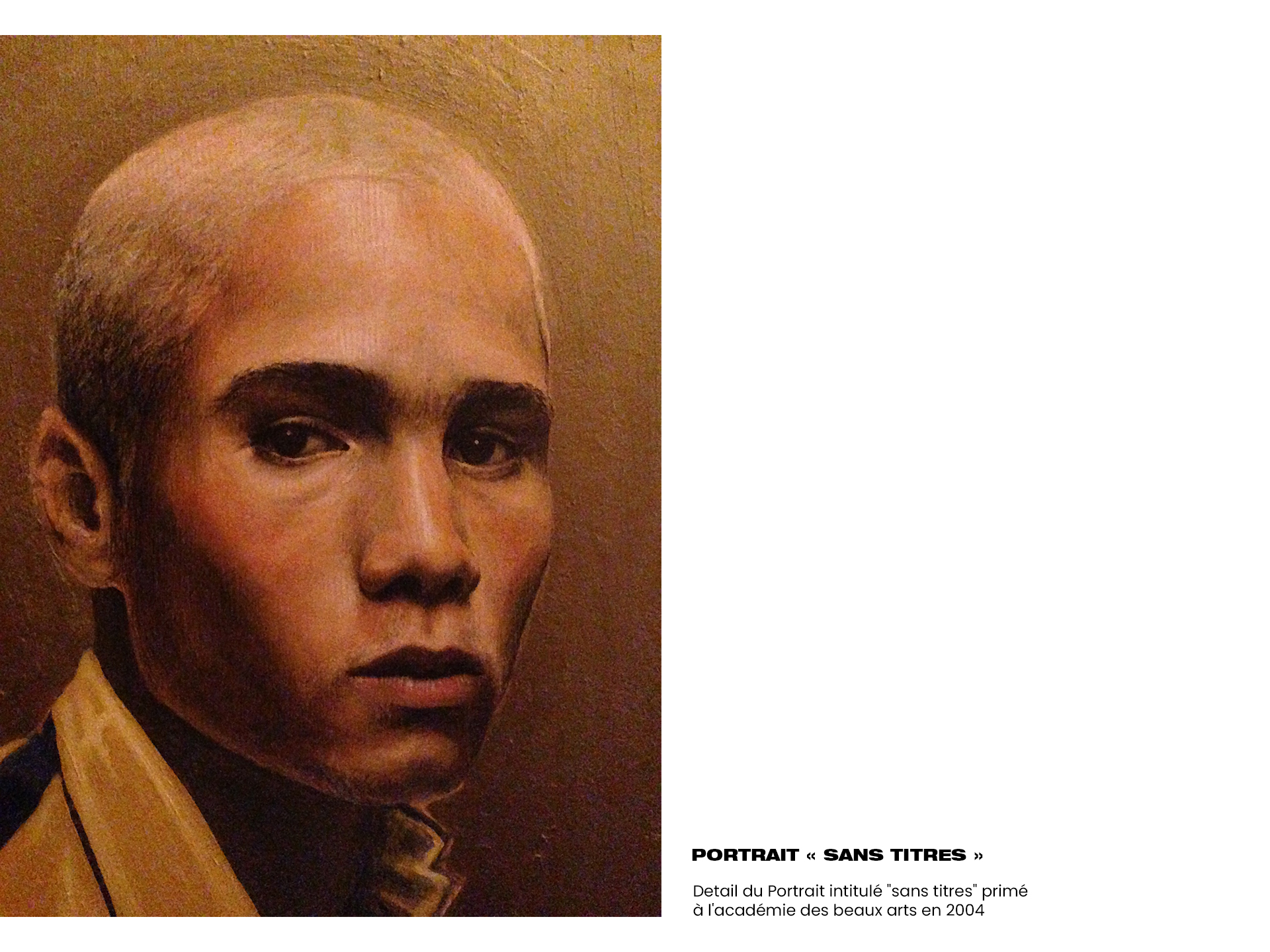

Déluge marque une page tournée, mais pas complètement ; on change d’éléments. Avant, c’était beaucoup plus le feu avec la poudre, et là, avec cette technique, c’est quelque chose de plus orienté vers l’eau. Comme pour Poussières, il y a aussi une connotation biblique : le déluge de Noé, qui recouvre la terre pendant quarante jours, est à la fois un élément destructeur et un événement créateur. Et les déluges, comme les guerres et les conflits, sont cycliques : il y en a toujours eu. Le déluge est un thème ancien qui traverse l’histoire et qu’il convient d’appréhender comme une catastrophe naturelle, tout comme la guerre. Cette série est aussi une démonstration de mon goût pour l’exploration technique. Renouveler la technique, c’est aussi renouveler mon rapport au sujet. Je tourne donc un peu les pages, mais je reste dans le même roman : disons que Déluge en est un nouveau chapitre. Et le prochain chapitre sera encore autre chose, mais pour l’instant, je peux seulement vous dire qu’il s’intitulera Les Disparitions. Actuellement, je suis aussi sur un grand tableau qui va mélanger toutes ces techniques et qui sera un portrait en buste, une allégorie. En 2004, j’avais été primé par l’Académie des Beaux-Arts dans l’art du portrait peint, et ça reste une chose que j’aime.

IN 2025, YOU EXPLORED A NEW TECHNIQUE WITH THE DÉLUGE SERIES, USING INK AND WATER ON CARDBOARD. DID THIS STEM FROM A DESIRE TO TURN THE PAGE AND MOVE TOWARD A NEW NARRATIVE?

In a way, the Déluge series remains focused on ruins and destruction. It’s true that some scenes may appear aquatic at first glance, but on closer inspection, you see cities destroyed by fire, bombed. The same theme persists, but I play between two opposing elements: water and fire, and this duality runs throughout the series. Déluge marks a turning of the page, but not entirely; we are changing the elements. Before, fire and powder dominated, and now, with this technique, it leans more toward water. As with Poussières, there’s also a biblical resonance: Noah’s flood, which covers the earth for forty days, is both destructive and creative. Floods, like wars and conflicts, are cyclical, they’ve always existed. The flood is an ancient theme that runs through history, and it should be understood as a natural catastrophe, much like war. This series also reflects my love for technical exploration. Renewing the technique is also a way of renewing my relationship to the subject. So I’m turning the page, but still within the same story: let’s say Déluge is a new chapter. The next chapter will be something different, but for now, all I can reveal is that it will be called Les Disparitions. I’m also currently working on a large painting that will combine all these techniques into a bust portrait, an allegory. Back in 2004, I was awarded by the Académie des Beaux-Arts for portrait painting, and it remains a practice I deeply enjoy.

DANS LE ROMANTISME, BEAUCOUP D’ARTISTES ONT REPRÉSENTÉ LES RUINES OU LES DÉLUGES POUR ÉVOQUER LE SENTIMENT DU SUBLIME. TOI AUSSI, ES-TU EN QUÊTE DE CE SENTIMENT CONTRASTÉ, ENTRE EFFROI ET BEAUTÉ ?

C’est important de voir les différentes nuances du romantisme à travers le monde, car il n’était pas le même partout. Le romantisme allemand est plus sombre, plus sourd, plus froid, centré sur la contemplation solitaire de la nature. À l’inverse, le romantisme français privilégie le mouvement, le contraste et l’émotion dramatique, avec une palette vive, beaucoup de rouges et de noirs – en lien avec le romantisme littéraire de Stendhal. L’Allemagne était un pays plus austère, plus protestant, d’où un romantisme plus introspectif, tandis que le romantisme français place l’homme et ses passions au centre, souvent dans des scènes héroïques ou tragiques. Si le romantisme français développe une narration, alors dans ce cas mon œuvre s’en éloigne, car elle s’inscrit plutôt dans l’ordre du silence. En revanche, je me reconnais dans le concept du sublime exploré par les Allemands, cette fascination pour la puissance de la nature et les ruines. Quand j’étais enfant à Beyrouth, je marchais la nuit dans une ville en grande partie détruite, et je trouvais cela sublime. C’était incroyablement beau, presque comme une planète oubliée, squelettique et morte. Parallèlement, le fait de savoir que la plupart des gens éviteraient ou déploreraient ces lieux rendait le moment et l’endroit encore plus intime et précieux pour moi. J’ai toujours été attirée par les grandes profondeurs, ce qui relie ma passion pour la spéléologie : explorer, fouiller, s’enfoncer dans les profondeurs de la Terre. Dans l’obscurité, certains éclats de lumière se révèlent dix fois plus forts, et c’est ce contraste entre lumière et ténèbres qui m’inspire profondément. La danse du blanc et du noir.

IN ROMANTICISM, MANY ARTISTS DEPICTED RUINS OR FLOODS TO EVOKE THE FEELING OF THE SUBLIME. DO YOU, TOO, PURSUE THIS CONTRAST BETWEEN AWE AND BEAUTY?

It’s important to consider the different nuances of Romanticism across the world, because it wasn’t the same everywhere. German Romanticism is darker, more muted, colder, centered on solitary contemplation of nature. In contrast, French Romanticism favors movement, contrast, and dramatic emotion, with a vivid palette, rich in reds and blacks – in line with the literary Romanticism of Stendhal, Le Rouge et le Noir. Germany was a more austere, Protestant country, which gave rise to a more introspective Romanticism, while French Romanticism places humans and their passions at the center, often in heroic or tragic scenes. If French Romanticism develops a narrative, my work moves away from that, it belongs more to the realm of silence. However, I identify with the German notion of the sublime, this fascination with the power of nature and the ruins it leaves behind. As a child in Beirut, I would walk at night through a city largely destroyed, and I found it sublime. It was incredibly beautiful, almost like a forgotten planet, skeletal and dead. At the same time, knowing that most people would avoid or lament these places made the moment and the space feel even more intimate and precious to me. I’ve always been drawn to great depths, which connects to my passion for caving: exploring, digging, delving into the Earth. In the darkness, certain glimmers of light appear ten times more intense, and it’s this contrast between light and shadow that profoundly inspires me. The dance of black and white.

TON ŒUVRE OSCILLE ENTRE EFFONDREMENT ET BEAUTÉ, DÉSESPOIR ET ESPOIR. TON REGARD SUR LE MONDE EST-IL PLUTÔT PESSIMISTE OU PORTEUR D’UNE ESPÉRANCE CACHÉE ? EXISTE-T-IL SELON TOI UNE RENAISSANCE APRÈS L’EFFONDREMENT ?

La notion de cycle, comme celle des saisons, et surtout beaucoup de jardinage, m’aident à répondre à cette question de manière rationnelle. À l’approche de l’hiver, on s’inquiète un peu pour les plantes ; puis il arrive, il est dur, mais on tient bon, parce que « l’hiver, c’est fait pour résister » (chanson de Mano Solo). Cet espoir inscrit dans le temps est déjà une forme d’optimisme. Je crois donc que l’optimisme n’est pas une posture naïve, mais une réponse nécessaire aux moments les plus sombres : plus l’angoisse est grande, plus il en faut. En ce sens, je pense qu’il faut placer l’optimisme là où on en a besoin, et je dirais que je suis optimiste, dans le sens où je me retrouve dans un optimisme de réaction. Le pessimisme, à l’inverse, m’a toujours semblé étrange. Souvent, les gens pessimistes tentent de vivre à l’avance ce qu’ils redoutent, pour ne pas être surpris. Mais ils finissent malgré tout par le vivre par anticipation et par procuration, parfois même deux fois. Il y a quelque chose de presque suicidaire dans cette attitude. Face aux conflits, aux violences ou aux effondrements sociétaux, je ne sais pas si ces événements annoncent une possible renaissance en mieux. Une renaissance, sûrement, mais je ne sais pas sous quelle forme. J’ai trop de pudeur pour m’avancer à placer un espoir concret sur ce qui viendra, car mon rôle n’est pas de prévoir, mais d’essayer de témoigner. Je ne fais que dessiner. Mais l’optimisme, même si fragile, est déjà une solution. Il ne garantit pas d’obtenir ce que l’on espère, mais il rend le présent plus vivable et les entreprises plus éclairées. C’est une façon de craquer une amulette.

YOUR WORK OSCILLATES BETWEEN COLLAPSE AND BEAUTY, DESPAIR AND HOPE. IS YOUR VIEW OF THE WORLD MORE PESSIMISTIC OR DOES IT CARRY A HIDDEN SENSE OF HOPE? DO YOU BELIEVE IN A FORM OF REBIRTH AFTER COLLAPSE?

The idea of cycles, like the seasons, and, above all, a lot of gardening, helps me answer this question in a rational way. As winter approaches, you worry a little about the plants; then it arrives, harsh and unforgiving, but you endure, because “winter is meant for resisting” (a song by Mano Solo). This sense of hope embedded in time is already a form of optimism. I believe optimism isn’t a naive stance, but a necessary response to the darkest moments: the greater the anxiety, the more hope is needed. In this sense, I place optimism where it’s needed, and I’d say I am optimistic, an optimism born of reaction. Pessimism, on the other hand, has always felt strange to me. Often, pessimistic people try to live in advance through what they fear, so they won’t be surprised. Yet they end up experiencing it anyway, by anticipation and proxy, sometimes twice over. There’s something almost self-destructive in that approach. When it comes to conflicts, violence, or societal collapse, I don’t know if these events herald a possible rebirth for the better. A rebirth, perhaps, but I cannot say in what form. I’m too cautious to project concrete hope onto the future, because my role isn’t to predict, but to bear witness. All I do is draw. Even so, optimism, even tentative, is already a form of solution. It doesn’t guarantee that what we hope for will come, but it makes the present more bearable and our efforts more enlightened. It’s like cracking open a talisman.

Détails de la série déluge

POUR CONCLURE, JE VOUDRAIS REVENIR AU TOUT DÉBUT DE CETTE HISTOIRE, À L’ENFANT DE 10 ANS QUE TU ÉTAIS. QUE LUI DIRAIS-TU POUR QU’IL PUISSE GRANDIR HEUREUX DANS UN MONDE SI FRACTURÉ ?

À vrai dire, je n’aurais rien à lui dire. C’est plutôt à moi de m’inspirer de lui pour apprendre à vieillir dans un monde comme celui-ci.

TO CONCLUDE, I’D LIKE TO GO BACK TO THE VERY BEGINNING OF THIS STORY, TO THE 10-YEAR-OLD CHILD YOU ONCE WERE. WHAT WOULD YOU SAY TO HIM SO HE COULD GROW UP HAPPY IN SUCH A FRACTURED WORLD?

To be honest, I wouldn’t say anything at all. Instead, it’s him who inspires me, I look to that child to learn how to grow old in a world like this.